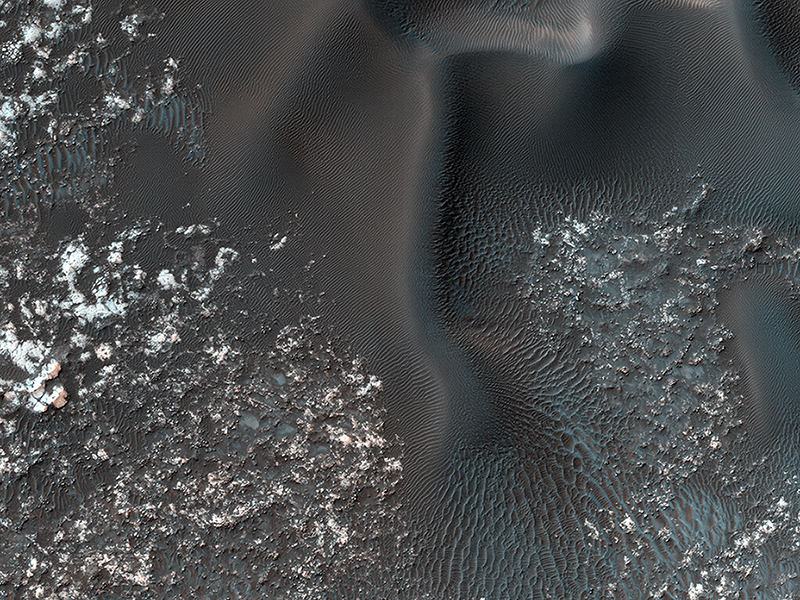

Kirby Runyon wrote:Opposing Dunes, Opposing Winds (ESP_049481_1310)

On the west (left) side of this image, fairly textbook-looking barchan sand dunes sit atop the bedrock. Barchan dunes pointing in the opposite direction are just a few kilometers away to the east.

In between these opposing barchan dunes are star dunes. Barchan dunes form when the sand-moving wind is fairly unidirectional. Star dunes, in contrast, form when the sand-moving wind comes from multiple directions—not all at once, but from varying directions at different times of day or year.

Where is the sand coming from? As with most places on Mars...well, that’s an area of on-going research. But the star dunes are telling us that this area seems to be accumulating sand.

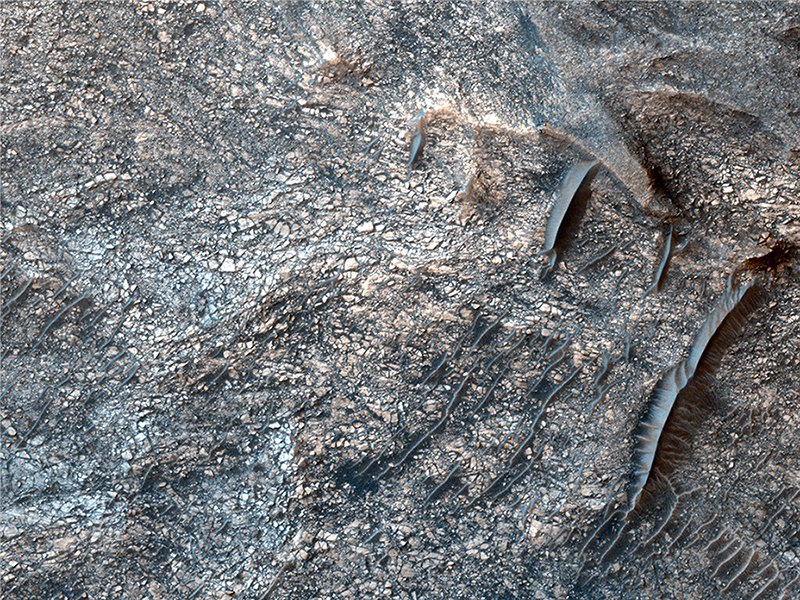

Kirby Runyon wrote:Exploring the Sandy Province of Herschel Crater (ESP_050159_1655)

While perhaps not awe-inspiringly beautiful, sand sheets can tell us about Mars’ current and past environmental conditions as a piece of the puzzle for understanding habitability.

This view shows the downwind stretches of a sand sheet in central part of the much larger Herschel Crater. This sandy province began kilometers upwind in a string of barchan sand dunes. As the north-to-south blowing wind weakened downwind, it could no longer fashion the sand into dunes but rather into amorphously-shaped sand sheets.

Having dunes upwind of sheets is the opposite situation Earth has, where upwind sand sheets evolve downwind into sand dunes. This mystery is receiving ongoing research to to understand these sandy differences between Earth and Mars.

Cathy Weitz wrote:Mixtures of Sulfates in Melas Chasma (ESP_051129_1705)

Many locations on Mars have sulfates, which are sedimentary rocks formed in water. Within Valles Marineris, the large canyon system that cuts across the planet, there are big and thick sequences of sulfates.

In this image, layering within the light-toned sulfate deposit is the result of different states of hydration. Some of the layers have sulfates with little water (known as monohydrated sulfates) whereas other layers have higher amounts of water (called polyhydrated sulfates). The different amounts of water within the sulfates may reflect changes in the water chemistry during deposition of the sulfates, or may have occurred after the sulfates were laid down when heat or pressure forced the water out of some layers, causing a decrease in the hydration state.

The CRISM instrument on MRO is crucial for telling scientists which type of sulfate is associated with each layer, because each hydration state will produce a spectrum with absorptions at specific wavelengths depending upon the amount of water contained within the sulfate.

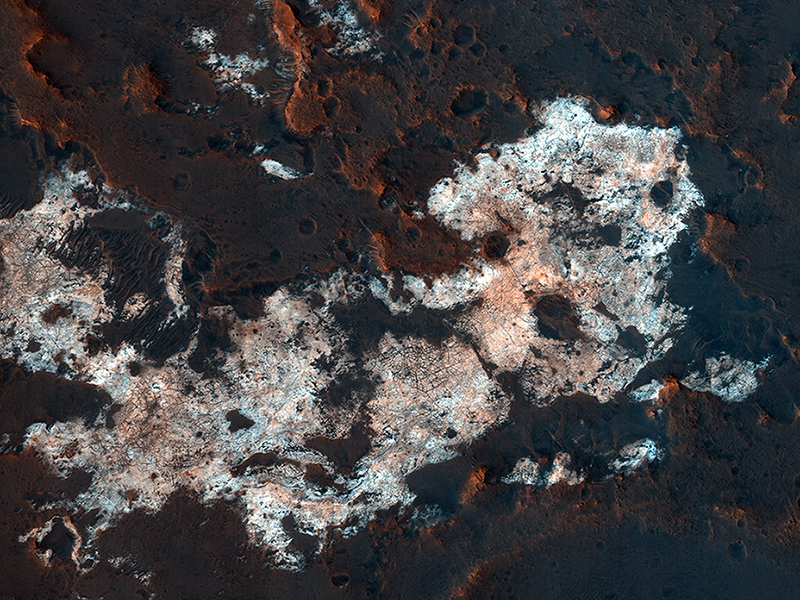

Paul Geissler wrote:Prospecting from Orbit (ESP_051153_2025)

The combination of morphological and topographic information from stereo images, as well as compositional data from near-infrared spectroscopy has been proven to be a powerful tool for understanding the geology of Mars.

Beginning with the OMEGA instrument on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter in 2003, the surface of Mars has been examined at near-infrared wavelengths by imaging spectrometers that are capable of detecting specific minerals and mapping their spatial extent. The CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars) instrument on our orbiter is a visible/near-infrared imaging spectrometer, and the HiRISE camera works together with it to document the appearance of mineral deposits detected by this orbital prospecting.

Mawrth Vallis is one of the regions on Mars that has attracted much attention because of the nature and diversity of the minerals identified by these spectrometers. It is a large, ancient outflow channel on the margin of the Southern highlands and Northern lowlands. Both the OMEGA and CRISM instruments have detected clay minerals here that must have been deposited in a water-rich environment, probably more than 4 billion years ago. For this reason, Mawrth Vallis is one of the two candidate landing sites for the future Mars Express Rover Mission planned by the European Space Agency.

This image was targeted on a location where the CRISM instrument detected a specific mineral called alunite, KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6. Alunite is a hydrated aluminum potassium sulfate, a mineral that is notable because it must have been deposited in a wet acidic environment, rich in sulfuric acid. Our image shows that the deposit is bright and colorful, and extensively fractured. The width of the cutout is 1.2 kilometers.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

<< Previous HiRISE Update