NASA JPL | Spitzer Mission News | 22 July 2010

Space Balls

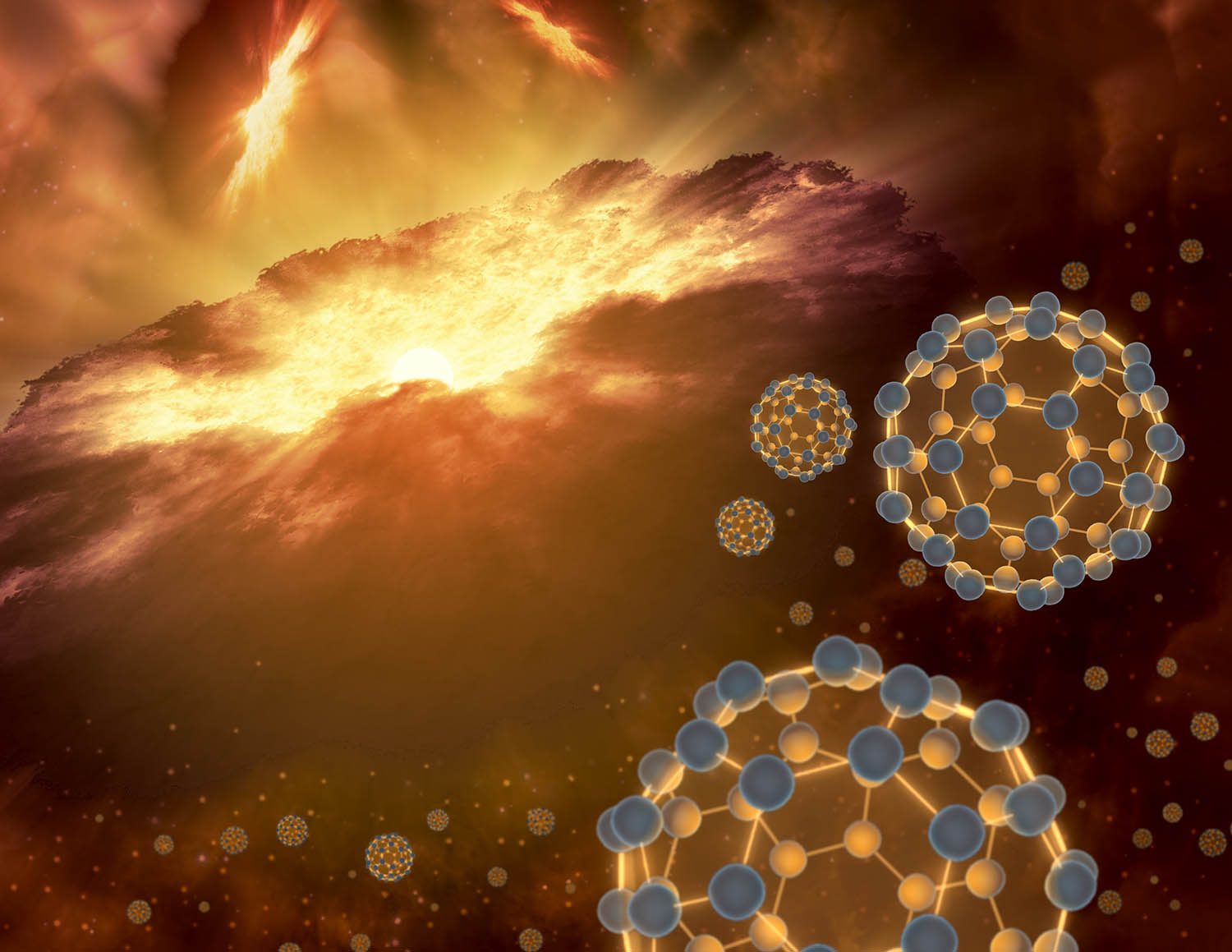

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has at last found buckyballs in space, as illustrated by this artist's conception showing the carbon balls coming out from the type of object where they were discovered -- a dying star and the material it sheds, known as a planetary nebula.

Buckyballs are made up of 60 carbon atoms organized into spherical structures that resemble soccer balls. They also look like Buckminister Fuller's architectural domes, hence their official name of buckministerfullerenes. The molecules were first concocted in a lab nearly 25 years ago, and were theorized at that time to be floating around carbon-rich stars in space.

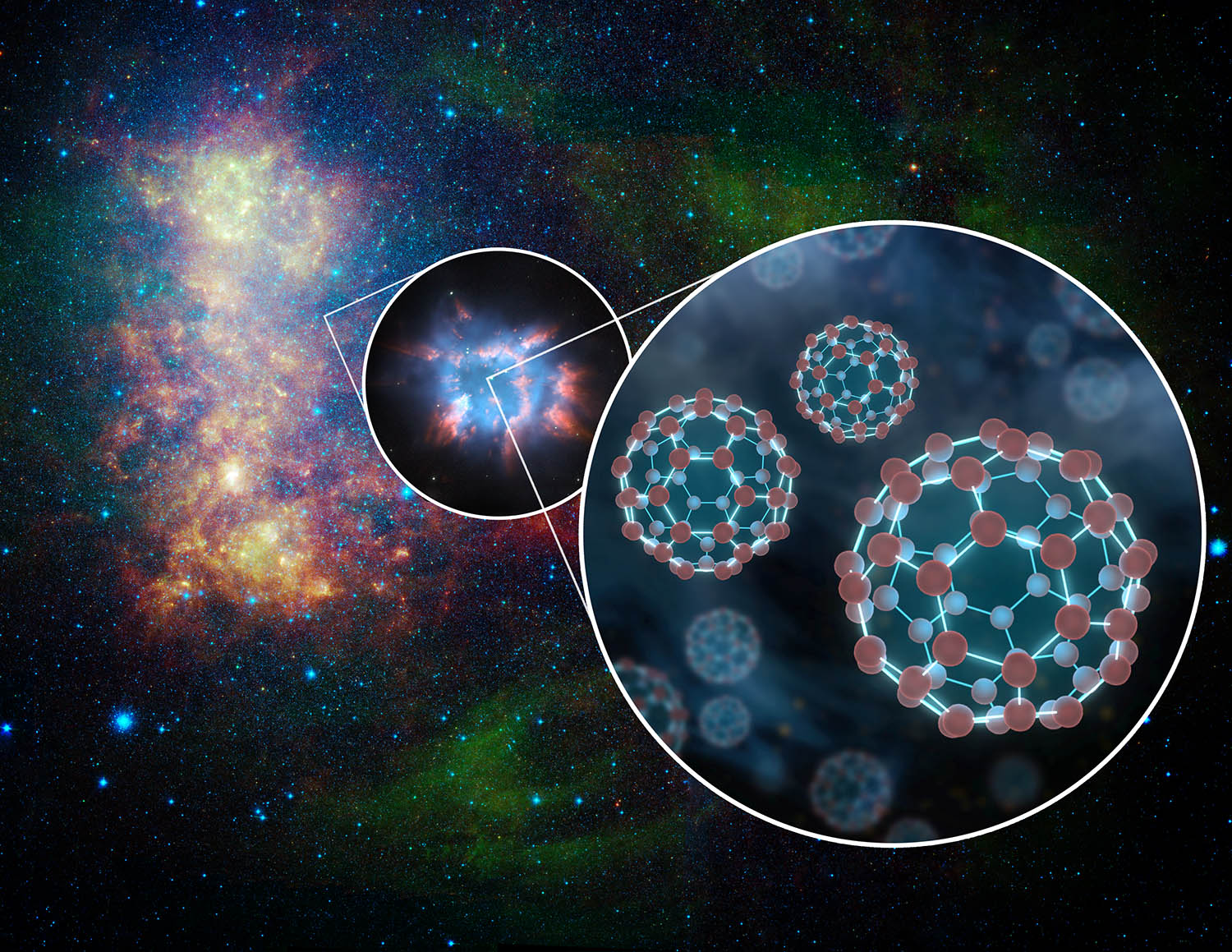

But it wasn't until now that Spitzer, using its sensitive infrared vision, was able to find convincing signs of buckyballs. The telescope found the molecules -- as well as their elongated, rugby-ball-like relatives, called C70 -- in the material around a dying star, or planetary nebula, called Tc 1. The star at the center of Tc 1 was once similar to our sun but as it aged, it sloughed off its outer layers, leaving only a dense white-dwarf star. Astronomers believe buckyballs were created in shed layers of carbon that blew off the star.

Tc 1 does not show up that well in images, so a picture of the NGC 2440 nebula, taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, was used in this artist's conception.

Illustration credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle (SSC)

Hubble image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI Jiggling Soccer-Ball Molecules in Space

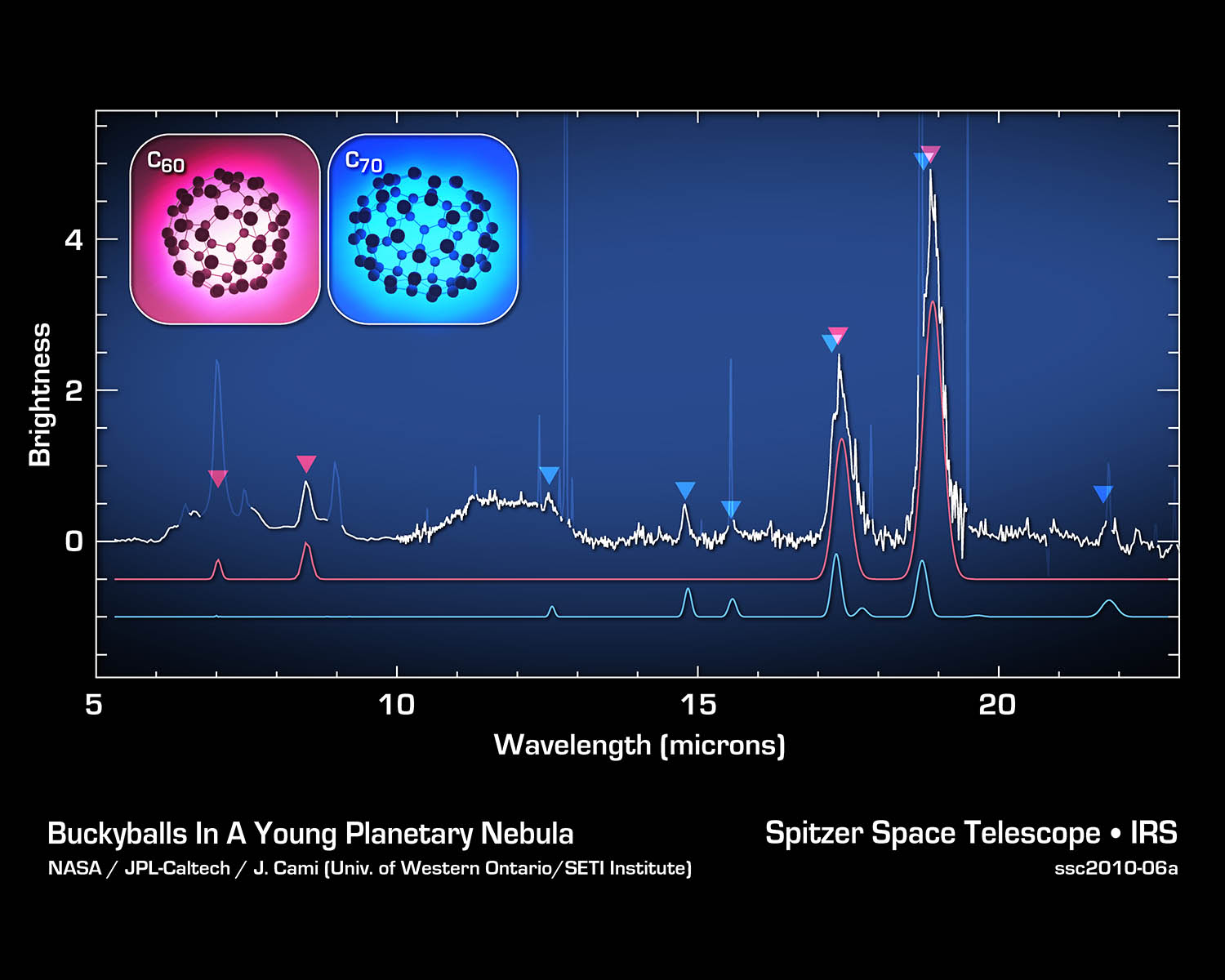

These data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope show the signatures of buckyballs in space. Buckyballs, also called C60 or buckministerfullerenes, after architect Buckminister Fuller's geodesic domes, are made of 60 carbon atoms structured like a black-and-white soccer ball. They were first discovered in a lab in 1985, but could not be definitively identified in space until now. Spitzer was able to find their spectral signatures -- along with the signatures of their rugby-ball-like relatives, called C70 -- by analyzing the infrared light from Tc 1, a planetary nebula consisting of material shed by a dying star.

Buckyballs jiggle, or vibrate, in a variety of ways -- 174 ways to be exact. Four of these vibrational modes cause the molecules to either absorb or emit infrared light. All four modes were detected by Spitzer.

The space telescope first gathered light from the area around the dying star -- specifically a region rich in carbon -- then, with the help of its spectrograph instrument, spread the light into its various components, or wavelengths. Astronomers studied the data, a spectrum like the one shown here, to identify signatures, or fingerprints, of molecules. The four vibrational modes of buckyballs are indicated by the red arrows. Likewise, Spitzer identified four vibrational modes of C70, shown by the blue arrows.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/J. Cami (Univ. of Western Ontario/SETI Institute)

Buckyballs Jiggle Like Jello (video)

Mini Soccer Balls in Space (video)