http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2011/04/fermilab-physicists-see-somethin.html?rss=1 wrote:

Fermilab Physicists See Something Weird ...

by Adrian Cho on 6 April 2011, 5:50 PM | Permanent Link | 4 Comments

<<The particle physics world is abuzz with the news that researchers at the United States's sole particle physics lab may have spotted a weird particle unlike any seen before. That prospect is so tantalizing it garnered coverage in The New York Times. However, the experimenters who made the measurements caution that the supposed signal could also be a product of unidentified inaccuracies in their modeling of their incredibly complex particle detector. Physicists would also have trouble explaining how they missed the particle before.

"I'm kind of surprised that [The New York Times] wrote about it; it must have been a slow news day," says Robert Roser, co-spokesperson for the 500-member team working with the CDF particle detector at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) in Batavia, Illinois, which made the observation. Still, he says, it's possible that the scientists have seen a new particle.

The result comes from CDF's analysis of billions of collisions of protons and antiprotons produced by Fermilab's Tevatron collider. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, energy equals mass, so those high-energy collisions can blast into fleeting existence massive subatomic particles not seen in the everyday world. Physicists then try to identify those particles by studying the combinations of more-familiar particles into which they decay.

In this case, experimenters searched for collisions that produced a particle called a W boson, which weighs about 87 times as much as a proton, and some other particle that disintegrates into two sprays of particles called "jets." A jet arises when a collision kicks out a particle called a quark. A quark cannot exist on its own, but must be bound to other quarks or an antiquark. So the energetic quark quickly rips more quarks and antiquarks out of the vacuum of empty space, and they instantaneously form particles called mesons, each containing a quark and an antiquark. From the energies and momenta of the two jets, researchers can infer the mass of the particle that produced them.

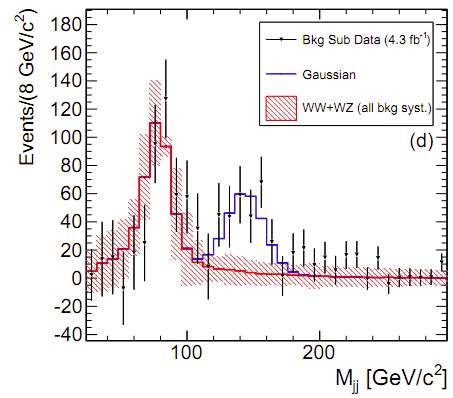

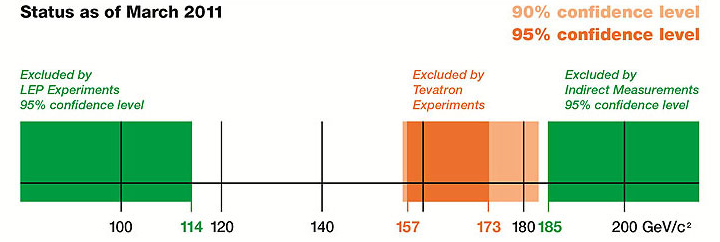

Shifting through their data, CDF researchers see about 250 events in which the jets seem to come from a particle weighing about 160 times as much as a proton, the team reports in a paper posted yesterday to the arXiv preprint server and in a talk today at Fermilab. The researchers estimate the statistical chances of random jets or jet pairs from other sources producing a fake signal that strong at one in 1300. "There's a lot of buzz here," says Joseph Lykken, a theorist at Fermilab who was not involved in the work. "I've gotten a lot of questions in that hallway."

So is it a done deal? Not quite, Lykken says. The analysis depends critically on physicists' understanding of jets, which are complex things. For example, the entire study grew out of an effort to spot events that produce two W bosons and one of the bosons produces a jet pair. So researcher must be absolutely sure that they haven't mistaken those two W events for ones containing a new particle. "The real question is how well do we understand that [background], not just theoretically, but in terms of how it will appear in the detector," Lykken says.

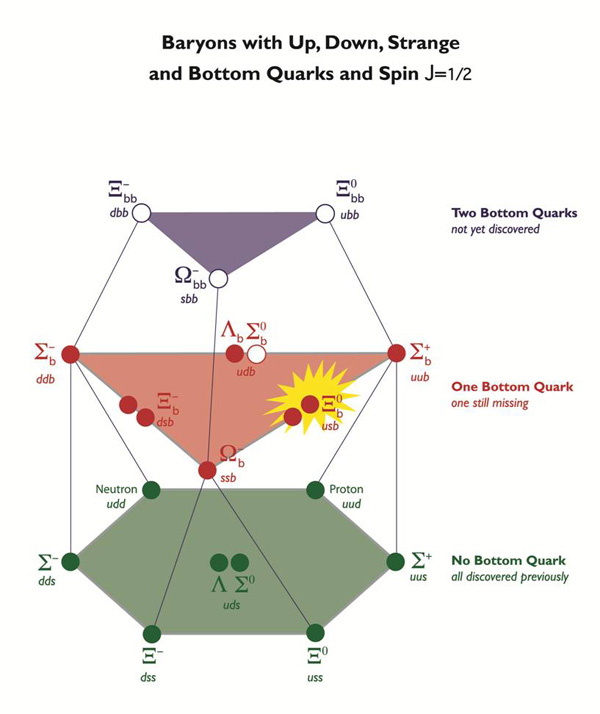

To have escaped notice until now, a new particle would also have to have some weird properties. For example, CDF researchers are searching for the long-sought Higgs boson, the key to physicists' understanding of mass, by looking for events in which it is produced along with a W boson and then decays into two jets specifically triggered by particles called bottom quarks. Those more-refined analyses have not seen the hypothetical new particle, so for some reason it must not decay into bottom quarks. Similarly, the hypothetical particle resembles the lighter W boson in its ability to decay into two jets. However, it apparently does not decay in the other ways that a W boson decays, or it would have been seen long ago.

Still, physicists say there's no reason to think that a wholly new type of particle won't have weird properties, Lykken says. And they expect the supposed signal to be confirmed or ruled out in short order. That's because CDF experimenters will soon analyze the other half of the data they've collected so far. More evidence will come from the Tevatron's other large particle detector, D0, which has generated a raw data set as big as CDF's. If the particle is really there, D0 should see it, too. If the signal is an artifact of the way CDF analyzes jets, then D0 would likely see nothing. "We understand that everybody is looking to us," says Dmitri Denisov, a physicist at Fermilab and co-spokesperson for the D0 team. "We hope that within a few weeks you'll be hearing from us.">>