This is it! You've looked at APOD all year, voted in 64 APOW and APOM polls, and now, it's time to select the Astronomy Picture of the Year for 2011!

Please vote for the THREE best APODs (image and text); there are 15 APODs in this poll selected from the winners of the APOM polls, plus three. All titles are clickable and link to the original APOD page.

Thank you!

________________________________________________________________

<< APOY 2010

What's happened to the Sun? Sometimes it looks like the Sun is being viewed through a large lens. In the above case, however, there are actually millions of lenses: ice crystals. As water freezes in the upper atmosphere, small, flat, six-sided, ice crystals might be formed. As these crystals flutter to the ground, much time is spent with their faces flat, parallel to the ground. An observer may pass through the same plane as many of the falling ice crystals near sunrise or sunset. During this alignment, each crystal can act like a miniature lens, refracting sunlight into our view and creating phenomena like parhelia, the technical term for sundogs. The above image was taken last year in Stockholm, Sweden. Visible in the image center is the Sun, while two bright sundogs glow prominently from both the left and the right. Also visible is the bright 22 degree halo -- as well as the rarer and much fainter 46 degree halo -- also created by sunlight reflecting off of atmospheric ice crystals.

Sometimes a morning sky can be a combination of serene and surreal. Such a sky perhaps existed before sunrise this past Sunday as viewed from a snowy slope in eastern Switzerland. Quiet clouds blanket the above scene, lit from beneath by lights from the village of Trübbach. A snow covered mountain, Mittlerspitz, poses dramatically on the upper left, hovering over the small town of Balzers, Liechtenstein far below. Peaks from the Alps can be seen across the far right, just below the freshly rising Sun. Visible on the upper right are the crescent Moon and the bright planet Venus. Venus will remain in the morning sky all month, although it will likely not be found in such a photogenic setting.

Credit & Copyright: Terje Sørgjerd; Music: Gladiator Soundtrack: Now we are Free

The spiky stars in the foreground of this sharp cosmic portrait are well within our own Milky Way Galaxy. The two eye-catching galaxies lie far beyond the Milky Way, at a distance of over 300 million light-years. Their distorted appearance is due to gravitational tides as the pair engage in close encounters. Cataloged as Arp 273 (also as UGC 1810), the galaxies do look peculiar, but interacting galaxies are now understood to be common in the universe. In fact, the nearby large spiral Andromeda Galaxy is known to be some 2 million light-years away and approaching the Milky Way. Arp 273 may offer an analog of their far future encounter. Repeated galaxy encounters on a cosmic timescale can ultimately result in a merger into a single galaxy of stars. From our perspective, the bright cores of the Arp 273 galaxies are separated by only a little over 100,000 light-years. The release of this stunning vista celebrates the 21st anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope in orbit.

Credit & Copyright: Daniel López, IAC; Music: Matti Paalanen, Angel's Tear (Aeon 2)

Thunderstorms almost spoiled this view of the spectacular June 15 total lunar eclipse. Instead, storm clouds parted for 10 minutes during the total eclipse phase and lightning bolts contributed to this dramatic skyview. Captured with a 30 second exposure, the scene also inspired what the editor considers may be the best title yet for a picture during the 16 year history of Astronomy Picture of the Day. (Title credit to Chris K.) Of course, the lightning reference clearly makes sense, and the shadow play of the dark lunar eclipse was widely viewed across planet Earth in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. The picture itself, however. was shot from the Greek Ikaria island at Pezi. That area is known as "the planet of the goats" because of the rough terrain and strange looking rocks.

NGC 3314 is actually two large spiral galaxies which just happen to almost exactly line up. The foreground spiral is viewed nearly face-on, its pinwheel shape defined by young bright star clusters. But against the glow of the background galaxy, dark swirling lanes of interstellar dust appear to dominate the face-on spiral's structure. The dust lanes are surprisingly pervasive, and this remarkable pair of overlapping galaxies is one of a small number of systems in which absorption of light from beyond a galaxy's own stars can be used to directly explore its distribution of dust. NGC 3314 is about 140 million light-years (background galaxy) and 117 million light-years (foreground galaxy) away in the multi-headed constellation Hydra. The background galaxy would span nearly 70,000 light-years at its estimated distance. A synthetic third channel was created to construct this dramatic new composite of the overlapping galaxies from two color image data in the Hubble Legacy Archive.

A quest to find planet Earth's darkest night skies led to this intriguing panorama. In projection, the mosaic view sandwiches the horizons visible in all-sky images taken from the northern hemisphere's Canary Island of La Palma (top) and the south's high Atacama Desert between the two hemispheres of the Milky Way Galaxy. The photographers' choice of locations offered locally dark skies enjoyed by La Palma's Roque de los Muchachos Observatory and Paranal Observatory in Chile. But it also allowed the directions to the Milky Way's north and south galactic poles to be placed near the local zenith. That constrained the faint, diffuse glow of the plane of the Milky Way to the mountainous horizons. As a result, an even fainter S-shaped band of light, sunlight scattered by dust along the solar system's ecliptic plane, can be completely traced through both northern and southern hemisphere night skies.

Scanning the skies for galaxies, Canadian astronomer Paul Hickson and colleagues identified some 100 compact groups of galaxies, now appropriately called Hickson Compact Groups. The four prominent galaxies seen in this intriguing telescopic skyscape are one such group, Hickson 44, about 100 million light-years distant toward the constellation Leo. The two spiral galaxies in the center of the image are edge-on NGC 3190 with its distinctive, warped dust lanes, and S-shaped NGC 3187. Along with the bright elliptical, NGC 3193 at the right, they are also known as Arp 316. The spiral in the upper left corner is NGC 3185, the 4th member of the Hickson group. Like other galaxies in Hickson groups, these show signs of distortion and enhanced star formation, evidence of a gravitational tug of war that will eventually result in galaxy mergers on a cosmic timescale. The merger process is now understood to be a normal part of the evolution of galaxies, including our own Milky Way. For scale, NGC 3190 is about 75,000 light-years across at the estimated distance of Hickson 44.

From Sagittarius to Carina, the Milky Way Galaxy shines in this dark night sky above planet Earth's lush island paradise of Mangaia. Familiar to denizens of the southern hemisphere, the gorgeous skyscape includes the bulging galactic center at the upper left and bright stars Alpha and Beta Centauri just right of center. About 10 kilometers wide, volcanic Mangaia is the southernmost of the Cook Islands. Geologists estimate that at 18 million years old it is the oldest island in the Pacific Ocean. Of course, the Milky Way is somewhat older, with the galaxy's oldest stars estimated to be over 13 billion years old. (Editor's note: This image holds the distinction of being selected as winner in the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition in the Earth and Space category.)

It's the bubble versus the cloud. NGC 7635, the Bubble Nebula, is being pushed out by the stellar wind of massive central star BD+602522. Next door, though, lives a giant molecular cloud, visible to the right. At this place in space, an irresistible force meets an immovable object in an interesting way. The cloud is able to contain the expansion of the bubble gas, but gets blasted by the hot radiation from the bubble's central star. The radiation heats up dense regions of the molecular cloud causing it to glow. The Bubble Nebula, pictured above in scientifically mapped colors to bring up contrast, is about 10 light-years across and part of a much larger complex of stars and shells. The Bubble Nebula can be seen with a small telescope towards the constellation of the Queen of Aethiopia (Cassiopeia).

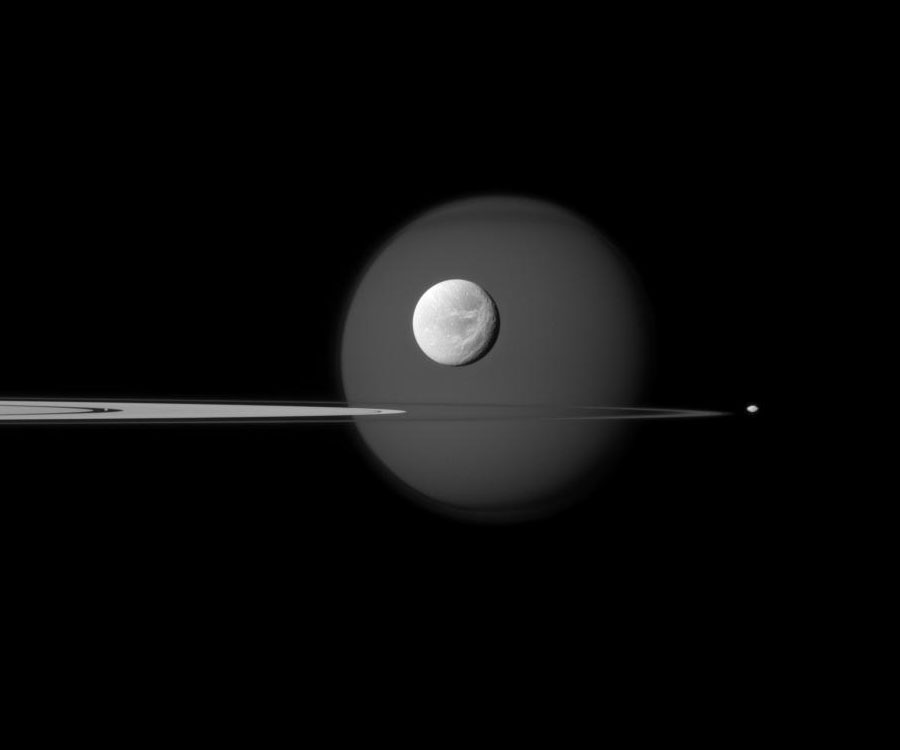

A fourth moon is visible on the above image if you look hard enough. First -- and furthest in the background -- is Titan, the largest moon of Saturn and one of the larger moons in the Solar System. The dark feature across the top of this perpetually cloudy world is the north polar hood. The next most obvious moon is bright Dione, visible in the foreground, complete with craters and long ice cliffs. Jutting in from the left are several of Saturn's expansive rings, including Saturn's A ring featuring the dark Encke Gap. On the far right, just outside the rings, is Pandora, a moon only 80-kilometers across that helps shepherd Saturn's F ring. The fourth moon? If you look closely in the Encke Gap you'll find a speck that is actually Pan. Although one of Saturn's smallest moons at 35-kilometers across, Pan is massive enough to help keep the Encke gap relatively free of ring particles.

Each day can have a beautiful ending as the Sun sets below the western horizon. This week, the setting Sun added naked-eye sunspots to its finale, as enormous active regions rotated across the dimmed, reddened solar disc. Near the Sun's center in this closing telephoto view from November 7th are sunspots in Active Region 1339. Responsible for a powerful X-class flare on November 3rd, Active Region 1339 is larger than Jupiter. In the foreground, the ruined tower of a medieval castle stands in dramatic silhouette. Located in Igersheim, Germany and traditionally known as castle Neuhaus, it might be named Sunspot Castle for this well-composed scene.

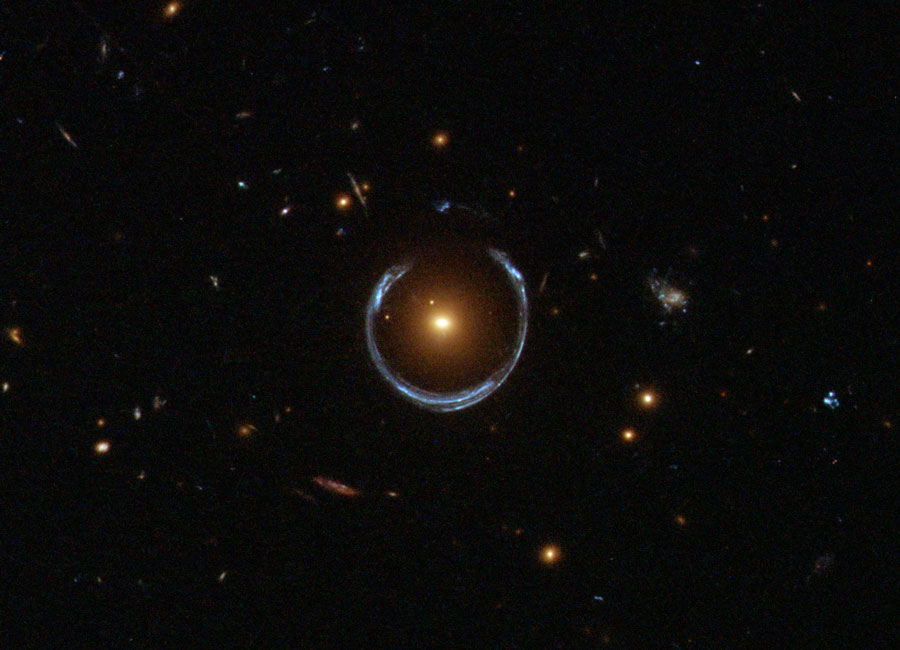

What's large and blue and can wrap itself around an entire galaxy? A gravitational lens mirage. Pictured above, the gravity of a luminous red galaxy (LRG) has gravitationally distorted the light from a much more distant blue galaxy. More typically, such light bending results in two discernible images of the distant galaxy, but here the lens alignment is so precise that the background galaxy is distorted into a horseshoe -- a nearly complete ring. Since such a lensing effect was generally predicted in some detail by Albert Einstein over 70 years ago, rings like this are now known as Einstein Rings. Although LRG 3-757 was discovered in 2007 in data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), the image shown above is a follow-up observation taken with the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Camera 3. Strong gravitational lenses like LRG 3-757 are more than oddities -- their multiple properties allow astronomers to determine the mass and dark matter content of the foreground galaxy lenses.

<< APOY 2010