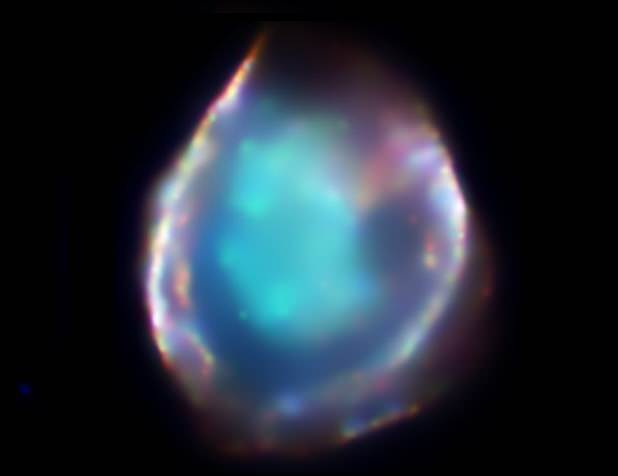

Type Ia supernovae (SN Ia’s) are the extraordinarily bright and remarkably similar “standard candles” astronomers use to measure cosmic growth, a technique that in 1998 led to the discovery of dark energy – and 13 years later to a Nobel Prize, “for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe.” The light from thousands of SN Ia’s has been studied, but until now their physics – how they detonate and what the star systems that produce them actually look like before they explode – has been educated guesswork.

Peter Nugent of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) heads the Computational Cosmology Center in the Lab’s Computational Research Division and also leads the Lab’s collaboration in the multi-institutional Palomar Transient Factory (PTF). On August 24 of this year, searching data as it poured into DOE’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) from an automated telescope on Palomar Mountain in California, Nugent spotted a remarkable object. It was shortly confirmed as a Type Ia supernova in the Pinwheel Galaxy, some 21 million light-years distant. That’s unusually close by cosmic standards, and the nearest SN Ia since 1986; it was subsequently given the official name SN 2011fe.

Nugent says, “We caught the supernova just 11 hours after it exploded, so soon that we were later able to calculate the actual moment of the explosion to within 20 minutes. Our early observations confirmed some assumptions about the physics of Type Ia supernovae, and we ruled out a number of possible models. But with this close-up look, we also found things nobody had dreamed of.”

“When we saw SN2011fe, I fell off my chair,” says PTF team member Mansi Kasliwal of the Carnegie Institution for Science and the California Institute of Technology. “Its brightness was too faint to be a supernova and too bright to be nova. Only follow-up observations in the next few hours revealed that this was actually an exceptionally young Type Ia supernova.”

Because they could closely study the supernova during its first few days, the team was able to gather the first direct evidence for what at least one SN Ia looked like before it exploded, and what happened next. Their results are reported in the 15 December, 2011, issue of the journal Nature.

Confirming a carbon-oxygen white dwarf

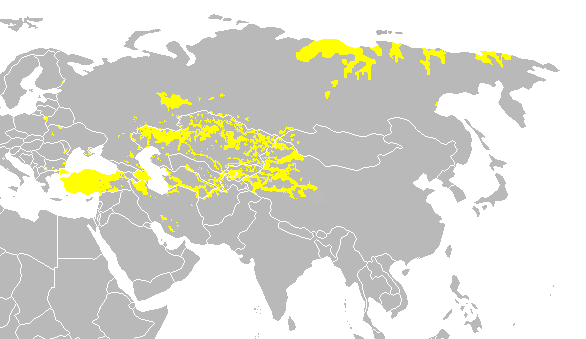

Scientists long ago developed models of Type Ia supernovae based on their evolving brightness and spectra. The models assume the progenitor is a binary system – about half of all stars are in binary systems – in which a very dense, very small white-dwarf star made of carbon and oxygen orbits a companion, from which it sweeps up additional matter. There’s a specific limit to how massive the white dwarf can grow, equal to about 1.4 times the mass of our sun, before it can no longer support itself against gravitational collapse.

“As it approaches the limit, conditions are met in the center so that the white dwarf detonates in a colossal thermonuclear explosion, which converts the carbon and oxygen to heavier elements including nickel,” says Nugent. “A shock wave rips through it and ejects the material in a bright expanding photosphere. Much of the brightness comes from the heat of the radioactive nickel as it decays to cobalt. Light also comes from ejecta being heated by the shock wave, and if this runs into the companion star it can be reheated, adding to the luminosity.”

By examining how SN 2011fe’s brightness evolved – its so-called early-time light curve – and the features of its early-time spectra, members of the PTF team were able to constrain how big the exploding star was, when it exploded, what might have happened during the explosion, and what kind of binary star system was involved.

The first observations of SN 2011fe were carried out at the Liverpool Telescope at La Palma in the Canary Islands, followed within hours by the Shane Telescope at Lick Observatory in California and the Keck I Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. These were shortly followed by NASA’s orbiting Swift Observatory.

Says Nugent, “We made an absurdly conservative assumption that the earliest luminosity was due entirely to the explosion itself and would increase over time in proportion to the size of the expanding fireball, which set an upper limit on the radius of the progenitor.”

Daniel Kasen, an assistant professor of astronomy and physics at the University of California at Berkeley and a faculty scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Nuclear Science Division, explains that “it only takes a few seconds for the shock wave to tear apart the star, but the debris heated in the explosion will continue to glow for several hours. The bigger the star, the brighter this afterglow. Because we caught this supernova so early, and with such sensitive observations, we were able to directly constrain the size of the progenitor.”

“Sure enough, it could only have been a white dwarf,” says Nugent. “The spectra gave us the carbon and oxygen, so we knew we had the first direct evidence that a Type Ia supernova does indeed start with a carbon-oxygen white dwarf.”

The expected and the unexpected

“The early-time light curve also constrained the radius of the binary system,” says Nugent, “so we got rid of a whole bunch of models,” ranging from old red giant stars to other white dwarfs in a so-called “double-degenerate” system.

Kasen explains that “if there was a giant companion star orbiting nearby, we should have seen some fireworks when the debris from the supernova crashed into it.” A red giant would have made the supernova brighter by several orders of magnitude early on. “Because we didn’t observe any bright flashes like that, we determined that the companion star could not have been much bigger than our sun.”

Nor was there much chance the companion was another white dwarf in a double-degenerate system, unless it had somehow avoided being torn apart and littering the surroundings with debris. A shock wave plowing through that kind of rubble would have produced a burst of early light the observers couldn’t have missed. So unless the companion was positioned almost exactly between the exploding star and the observers on Earth, closer to it than a 10th the diameter of our sun – an unlikely set of circumstances – the white dwarf’s companion had to be a main-sequence star.

While these observations pointed to a “normal” SN Ia, the way the white dwarf exploded held surprises. Typical of what would be expected, early spectra obtained by the Lick three-meter telescope showed many intermediate-mass elements spewing out of the expanding fireball, including ionized oxygen, magnesium, silicon, calcium, and iron, traveling 16,000 kilometers a second – more than five percent of the speed of light. Yet some oxygen was traveling much faster, at over 20,000 kilometers a second.

“The high-velocity oxygen shows that the oxygen wasn’t evenly distributed when the white dwarf blew up,” Nugent says, “indicating unusual clumpiness in the way it was dispersed.” But more interesting, he says, is that “whatever the mechanism of the explosion, it showed a tremendous amount of mixing, with some radioactive nickel mixed all the way to the photosphere. So the brightness followed the expanding surface almost exactly. This is not something any of us would have expected.”

PTF team member Mark Sullivan of the University of Oxford says, “Understanding how these giant explosions create and mix materials is important because supernovae are where we get most of the elements that make up the Earth and even our own bodies – for instance, these supernovae are a major source of iron in the universe. So we are all made of bits of exploding stars.”

“It is rare that you have eureka moments in science, but it happened four times on this supernova,” says Andy Howell, coleader of PTF’s SN Ia team: “The super-early discovery; the crazy first spectrum; when we figured out it had to be a white dwarf; and then, the Holy Grail, when we figured out details of the second star.”

Howell adds, “We’re like Captain Ahab … except our white whale is a white dwarf. We’re obsessed with proving they cause supernovae, but the evidence has been eluding us for decades.” This time, he says, “We got our whale … and we lived.”

“This first close SN Ia in the era of modern instrumentation will undoubtedly become the best-studied thermonuclear supernova in history,” the PTF team notes in their Nature paper, and “will form the new foundation upon which our knowledge of more distant Type Ia supernovae is built.”

Two decades after the Berkeley-Lab-based Supernova Cosmology Project, led by 2011 Nobel Prize-winner in Physics Saul Perlmutter, proved that Type Ia supernovae could be used to measure the expansion history of the universe, Berkeley Lab astrophysicists and computer scientists have finally gotten a close-up look at what these remarkable cosmic mileposts really look like.

Look at these stepped gables on the Hanseatic buildings of the city of Bruges in Belgium ( or Flanders). The light curve of the supernova resembles such stepped gables to me!

Look at these stepped gables on the Hanseatic buildings of the city of Bruges in Belgium ( or Flanders). The light curve of the supernova resembles such stepped gables to me!