http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crab_Nebula#Origins_and_history_of_observation wrote:

[img3="

The Earl of Rosse observed the Crab nebula at Birr Castle in 1844 using a 36-inch telescope, and referred to the object as the "Crab Nebula" because a drawing he made of it looked like a crab (he observed it again later, in 1848, using a 72-telescope and could not confirm the supposed resemblance, but the name stuck nevertheless)."]

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... 1rosse.jpg[/img3]

<<In 1757, Alexis Clairaut reexamined the calculations of Edmund Halley and predicted the return of Halley's Comet in late 1758. The exact time of the comet's return required the consideration of perturbations to its orbit caused by planets in the Solar System such as Jupiter, which Clairaut and his two colleagues Jérôme Lalande and Nicole-Reine Lepaute carried out more precisely than Halley, finding that the comet should appear in the constellation of Taurus. It is in searching in vain for the comet that Charles Messier found the Crab nebula, which he at first thought to be Halley's comet. After some observation, noticing that the object that he was observing was not moving across the sky, Messier concluded that the object was not a comet. Messier then realised the usefulness of compiling a catalogue of celestial objects of a cloudy nature, but fixed in the sky, to avoid incorrectly cataloging them as comets. Messier catalogued [the Crab nebula] as the first entry in his catalogue of comet-like objects

Changes in the cloud, suggesting its small extent, were discovered by Carl Lampland in 1921. That same year, John Charles Duncan demonstrated that the remnant is expanding, while Knut Lundmark noted its proximity to the guest star of 1054, but did not mention the comments of his two colleagues. In 1928, Edwin Hubble proposed associating the cloud to the star of 1054, an idea which remained confidential until the nature of supernovae was understood, and it was Nicholas Mayall who indicated that the star of 1054 was undoubtedly the supernova whose explosion produced the Crab Nebula. The search for historical supernovae started at that moment: seven other historical sightings have been found by comparing modern observations of supernova remnants with astronomical documents of past centuries. Given its great distance, the daytime "guest star" observed by the Chinese could only have been a supernova—a massive, exploding star, having exhausted its supply of energy from nuclear fusion and collapsed in on itself. Recent analysis of historical records have found that the supernova that created the Crab Nebula probably appeared in April or early May, rising to its maximum brightness of between apparent magnitude −7 and −4.5 (brighter than everything in the night sky except the Moon) by July. The supernova was visible to the naked eye for about two years after its first observation. Thanks to the recorded observations of Far Eastern and Middle Eastern astronomers of 1054, Crab Nebula became the first astronomical object recognized as being connected to a supernova explosion.

In the 1960s, because of the prediction and discovery of pulsars, the Crab nebula again became a major centre of interest. It was then that Franco Pacini predicted the existence of a neutron star for the first time, which would explain the brightness of the cloud. This neutron star was observed shortly afterwards in 1968, a shining confirmation of the theory of the formation of these objects at the time of certain supernovae. The discovery of the Crab pulsar, and the knowledge of its exact age (almost to the day) allows for the verification of basic physical properties of these objects, such as characteristic age and spin-down luminosity, the orders of magnitude involved (notably the strength of the magnetic field), along with various aspects related to the dynamics of the remnant. The particular role of this supernova to the scientific understanding of supernova remnants was crucial, as no other historical supernova created a pulsar whose precise age we can know for certain. The only possible exception to this rule would be SN 1181 whose supposed remnant, 3C58, is home to a pulsar, but its identification using Chinese observations from 1181 is sometimes contested.>>

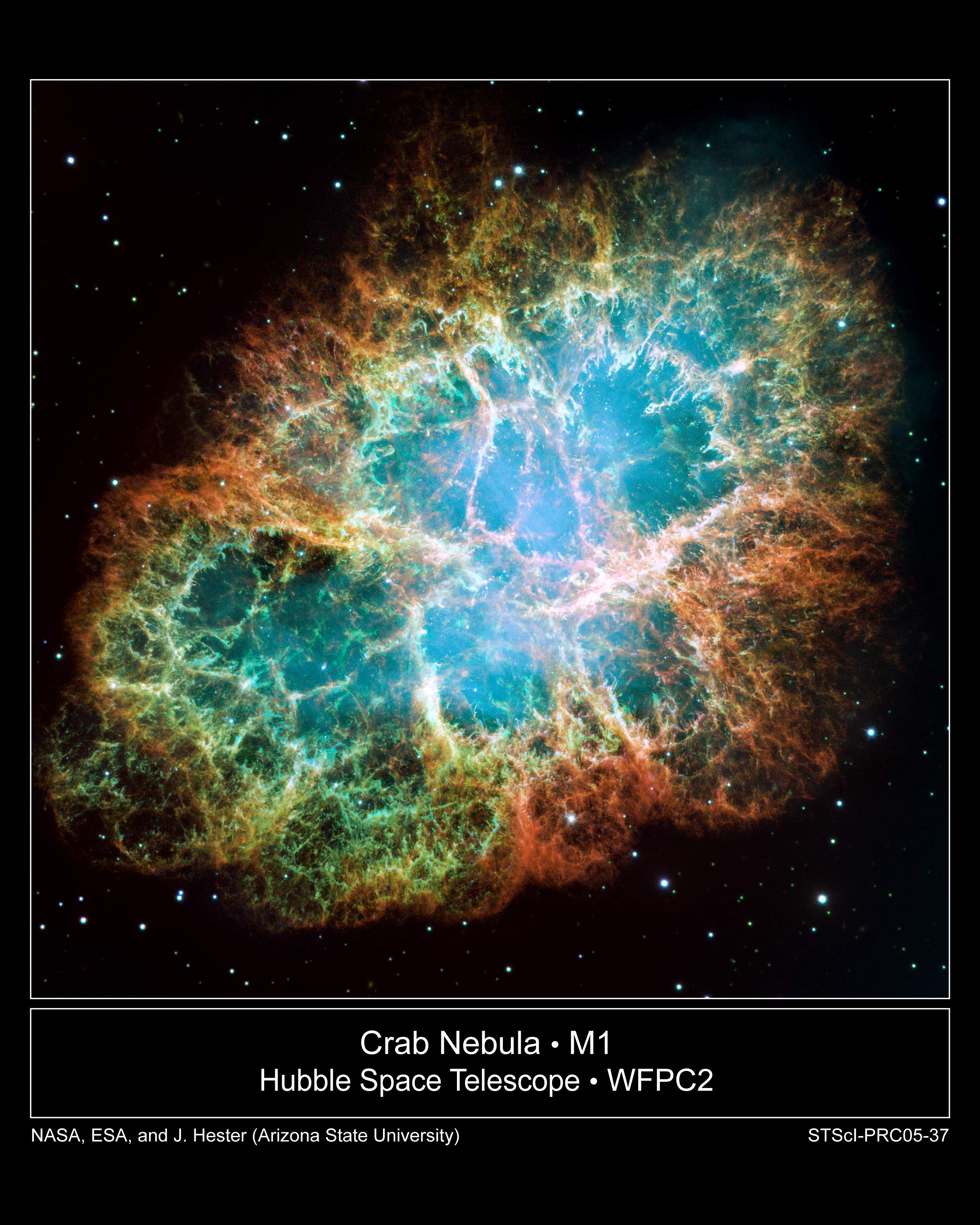

M1: The Crab Nebula from Hubble

M1: The Crab Nebula from Hubble