Page 1 of 1

APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 4:07 am

by APOD Robot

Lynds Dark Nebula 183

Explanation: Beverly Lynds

Lynds Dark Nebula 183

Explanation: Beverly Lynds Dark Nebula 183 lies a mere 325 light-years away, drifting high above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy. Obscuring the starlight behind it

when viewed at optical wavelengths, the dark, dusty molecular cloud itself seems starless. But far infrared

explorations reveal dense clumps within, likely stars in the

early stages of formation as enhanced regions of the cloud undergo gravitational collapse. One of the closest molecular clouds, it is seen toward the constellation

Serpens Caput. This sharp cosmic cloud portrait spans about half a degree on the sky. That's about 3 light-years at the estimated distance of

Lynds Dark Nebula 183.

[/b]

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 10:18 am

by Ann

What an interesting APOD!

Me being me, it goes without saying that the stars interest me because they are blue. The brightest of the stars is Mu Serpens, a relatively hot and blue A0-type star with a negative B-V index and a visible-light luminosity of about 86 times solar. Two of the other blue stars in the picture are lesser A-type stars, cooler and fainter than Mu Serpens, but still a lot hotter and brighter than the Sun. The blue star at bottom center is more distant than the three others and does not belong to the same group or cluster.

But the other three must have been born at more or less the same time. According to today's caption, the distance to LDN 183 is 325 light-years, too far away to have anything to do with the formation of Mu Serpens and its blue siblings, which reside at about 170 light-years. But guess what? The blue odd-on-out at bottom center of today's APOD, HD 141569, is a B9 star located at about 380 light-years, clearly farther away than LDN 183, but still possibly connected with it. This star just might have been born from LDN 183, which, in that case, would have shrunk in size. And it would appear that the far side of LDN 183 is the one that has retreated, if HD 141569 was indeed born from it.

The Lagoon Nebula with cluster NGC 6530.

Photo: Adam Block.

I think you can see the same phenomenon in other regions of star formation. One of more stars are born from a dust cloud, and the nebula that they were born from shrinks accordingly and retreats from the stars.

One example might be the Lagoon Nebula. In the eastern (left) part of the nebula you can find a star cluster, NGC 6530, that was recently born from the nebula. I believe that NGC 6530 is located in front of the remaining nebula, which has shrunk and retreated in response to the formation of the star cluster.

Ann

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 11:00 am

by r937

high above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy

oh, please... this is nonsense

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 12:38 pm

by heehaw

When I was a summer student at Kitt Peak National Observatory (about 1964), I vividly remember Roger Lynds showing us an utterly strange astronomical photograph that his wife Beverly Lynds had taken: it showed a 'nebulosity' different from any ever seen before: it was like an arc on the sky. No one had any idea what it could be! Well, it was eventually years later realized to be a gravitationally-lensed distant galaxy.

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 2:39 pm

by geckzilla

r937 wrote:high above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy

oh, please... this is nonsense

If you want to help, you could add a small explanation of what you mean. Otherwise, it kinda makes you look like a bit of a jerk, especially given your short posting history of only speaking up to offer acerbic criticism.

Gravitational Lynds

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 4:14 pm

by neufer

heehaw wrote:

When I was a summer student at Kitt Peak National Observatory (about 1964), I vividly remember Roger Lynds showing us an utterly strange astronomical photograph that his wife Beverly Lynds had taken: it showed a 'nebulosity' different from any ever seen before: it was like an arc on the sky. No one had any idea what it could be! Well, it was eventually years later realized to be a gravitationally-lensed distant galaxy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twin_Quasar wrote:

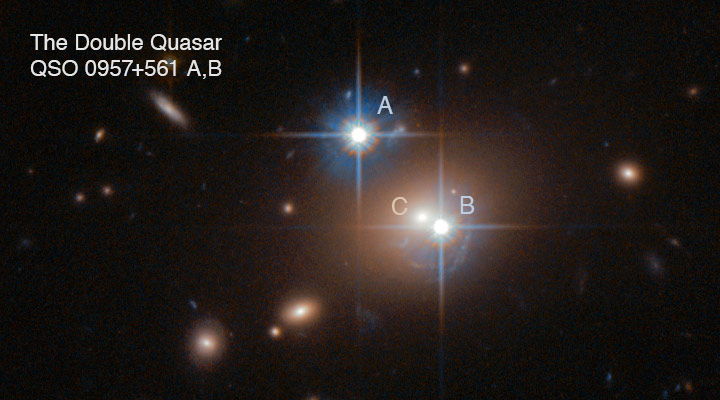

In this new Hubble image two objects are clearly visible, shining brightly. When they were first discovered in 1979, they were thought to be separate objects — however, astronomers soon realised that these twins are a little too identical! They are close together, lie at the same distance from us, and have surprisingly similar properties. They are in fact the same object. These cosmic doppelgangers make up a double quasar known as QSO 0957+561, also known as the "Twin Quasar", which lies just under 9 billion light-years from Earth. Quasars are the intensely powerful centres of distant galaxies. So, why are we seeing this quasar twice? Some 4 billion light-years from Earth — and directly in our line of sight — is the huge galaxy YGKOW G1.

This galaxy was the first ever observed gravitational lens. The Twin Quasar's two images are separated by 6 arcseconds. Both images have an apparent manitude of 17, with the A component having 16.7 and the B component having 16.5. There is a 417 ± 3 day time lag between the two images.

The quasars QSO 0957+561A/B were discovered in early 1979 by an Anglo-American team around Dennis Walsh, Robert Carswell and Ray Weyman, with the aid of the 2.1 m Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona/USA. The team noticed that the two quasars were unusually close to each other, and that their redshift and visible light spectrum were surprisingly similar. They published their suggestion of "the possibility that they are two images of the same object formed by a gravitational lens". The Twin Quasar was one of the first directly observable effects of gravitational lensing, which was described in 1936 by Albert Einstein as a consequence of his 1916 General Theory of Relativity, though in that 1936 paper he also predicted "Of course, there is no hope of observing this phenomenon directly."

Critics however identified a difference in appearance between the two quasars in radio frequency images. In mid 1979 a team led by David Roberts at the VLA (Very Large Array) near Socorro, New Mexico/USA discovered a relativistic jet emerging from quasar A with no corresponding equivalent in quasar B. Furthermore, the distance between the two images, 6 arcseconds, was too great to have been produced by the gravitational effect of the galaxy G1, a galaxy identified near quasar B.

Young et al. discovered that galaxy G1 is part of a galaxy cluster which increases the gravitational deflection and can explain the observed distance between the images. Finally, a team led by Marc V. Gorenstein observed essentially identical relativistic jets on very small scales from both A and B in 1983 using VLBI (Very Long Baseline Interferometry). The difference between the large-scale radio images is attributed to the special geometry needed for gravitational lensing, which is satisfied by the quasar but not by all of the extended jet emission seen by the VLA near image A.

Slight spectral differences between quasar A and quasar B can be explained by different densities of the intergalactic medium in the light paths, resulting in differing extinction. 30 years of observation made it clear that image A of the quasar reaches earth about 14 months earlier than the corresponding image B, resulting in a difference of path length of 1.1 ly.

In 1996, a team at Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics led by Rudy E. Schild discovered an anomalous fluctuation in one image's lightcurve, which led to a controversial and unconfirmable theory that there is a planet approximately three Earth masses in size in the lensing galaxy. The results remain speculative because the chance alignment that led to its discovery will never happen again. If it could be confirmed, however, it would make it the most distant known planet, 4 billion ly away. In 2006, R. E. Schild suggested that the accreting object at the heart of Q0957+561 is not a supermassive black hole, as is generally believed for all quasars, but a magnetospheric eternally collapsing object. Schild's team at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics asserted that "this quasar appears to be dynamically dominated by a magnetic field internally anchored to its central, rotating supermassive compact object" (R. E. Schild).>>

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 5:12 pm

by Ann

Fascinating, Art. I guess that the twin lensed quasars are the bluish "stars" near the center of the image. One of the quasars is apparently superimposed on a galaxy.

Or - no, wait! The quasars must be the two white "stars" apparently superimposed on the center of a galaxy!

Or is that another no-no? One of the white "stars" apparently superimposed on the center of the galaxy doesn't seem to have diffraction spikes. So that "star" is a normal, bright but not overwhelmingly bright, galactic core, then? Not a quasar?

Ann

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 5:27 pm

by ta152h0

Darkness arriving at the speed of light

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 5:42 pm

by Zuben L. Genubi

What I have for a long time wanted to know is how dense these molecular clouds are. From a great distance, they obscure the stars behind them, but is this because we observe through the entire depth of the cloud? If I were to fly my space ship through the thickest part of a molecular cloud (and obviously, I don't actually have a space ship, or I wouldn't have to ask!) would it be akin being in a pea soup fog at night, or would it be more like flying through a wispy mist?

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 7:33 pm

by neufer

Ann wrote:

Fascinating, Art. I guess that the twin lensed quasars are the bluish "stars" near the center of the image. One of the quasars is apparently superimposed on a galaxy. Or - no, wait! The quasars must be the two white "stars" apparently superimposed on the center of a galaxy! Or is that another no-no? One of the white "stars" apparently superimposed on the center of the galaxy doesn't seem to have diffraction spikes. So that "star" is a normal, bright but not overwhelmingly bright, galactic core, then? Not a quasar?

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 8:36 pm

by De58te

Zuben L. Genubi wrote:What I have for a long time wanted to know is how dense these molecular clouds are. From a great distance, they obscure the stars behind them, but is this because we observe through the entire depth of the cloud? If I were to fly my space ship through the thickest part of a molecular cloud (and obviously, I don't actually have a space ship, or I wouldn't have to ask!) would it be akin being in a pea soup fog at night, or would it be more like flying through a wispy mist?

From the infrared explorations link;

L183 (L134N) Revisited. II. The dust content

Pagani, L.; Bacmann, A.; Motte, F.; Cambrésy, L.; Fich, M.; Lagache, G.; Miville-Deschênes, M. -A.; Pardo, J. -R.; Apponi, A. J.

Abstract

We present here a complete dust map of L183 (=L134N) with opacities ranging from AVb = 3 to 150 mag. Five peaks are identified as being related to known molecular peaks and among these dust peaks two are liable to form stars. The main peak is a prestellar core with a density profile proportional to r-1 up to a radius of ̃4500 AU and the northern peak could possibly be on its way to form a prestellar core. If true, this is the first example of the intermediate steps between cloud cores and prestellar cores during the quasi-static contraction.

[I assume that if the cloud is nearly a prestellar core, it would look like pea soup if you sail through it. ]

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sat Oct 21, 2017 10:53 pm

by Zuben L. Genubi

Cool! Thanks.

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sun Oct 22, 2017 5:11 pm

by Case

r937 wrote:high above the plane of our Milky Way Galaxy

oh, please... this is nonsense

LDN 183 does lie higher above the galactic plane than the Sun in the absolute sense, and as such we view it to be

at 37° above the galactic plane from our perspective. For reference, LDN 183

lies close to binary star system

μ Ser in line of sight, which is about half as distant.

With the Milky Way disk in the order of a 1000 ly thick and the Sun a bit (

56 ly) above the plane, a nebula at an angle of 37° and at a distance of 325 ly, would then be about

298 250 ly above the plane,

if my trigonometry holds up.

High above the plane? Sure. Above the disk? Not so much. Too close for that.

geckzilla wrote:acerbic criticism.

I had to

look that up. Expanding my english vocabulary one word at the time.

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sun Oct 22, 2017 5:22 pm

by neufer

Case wrote:

LDN 183 does lie higher above the galactic plane than the Sun in the absolute sense, and as such we view it to be

at 37° above the galactic plane from our perspective. For reference, LDN 183

lies close to binary star system

μ Ser in line of sight, which is about half as distant.

With the Milky Way disk in the order of a 1000 ly thick and the Sun a bit (

56 ly) above the plane, a nebula at an angle of 37° and at a distance of 325 ly, would then be about 298 ly above the plane, if my trigonometry holds up.

- 252 ly above the plane = 56 + 325 sin(37°).

[You made the common mistake of using tangent rather than sin.]

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Sun Oct 22, 2017 11:35 pm

by Case

Thanks for the correction, I should know that. I’ll edit. (I guess the error wasn’t big enough for my own ‘this can’t be right’ gut feeling.)

Re: APOD: Lynds Dark Nebula 183 (2017 Oct 21)

Posted: Mon Oct 23, 2017 8:41 pm

by r937

Case wrote:High above the plane? Sure. Above the disk? Not so much.

thank you

and kudos for the wonderful diagram

‘this can’t be right’ gut feelings FTW !!!

Lynds Dark Nebula 183

Lynds Dark Nebula 183