JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases 2010

WISE: NGC 6744: A Sibling of the Milky Way

NGC 6744: A Sibling of the Milky Way - 04 June 2010

NGC 6744: A Sibling of the Milky Way

This image of spiral galaxy NGC 6744 from NASA’s WISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer) is a mosaic of frames covering an area 3 full Moons tall and 3 full Moons wide (1.56 x 1.56 degrees). It is located in a constellation in the Southern sky, Pavo, whose name is Latin for peacock.

There are relatively few large spiral galaxies in the local Universe (within about 40 million light-years of the Local Group of galaxies). At a distance from our Solar System of about 30 million light-years, NGC 6744 is one of the galaxies in the local Universe most like the Milky Way. So if there are observers somewhere in this sibling galaxy looking back at the Milky Way they might see a very similar image.

Its disk is about 175,000 light-years across, larger than the Milky Way Galaxy. So it is kind of like a big brother of the Milky Way. It has an elongated (barred) core and distinct spiral arms. The spiral arms of the disk are the sites of star formation within the galaxy and are very dusty. Dust and star formation go together hand-in-hand. Dust in star forming regions is relatively warm (temperatures of hundreds of Kelvins) and shows up as green and red in this infrared image from WISE. Throughout the disk and core are many, many older generations of stars whose temperatures are in the thousands of Kelvins. These stars are color-coded blue and cyan in this image.

This image was made from observations by all four infrared detectors aboard WISE. Blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is primarily light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is primarily emission from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

WISE: Comet 65/P Gunn

Comet 65/P Gunn - 11 June 2010

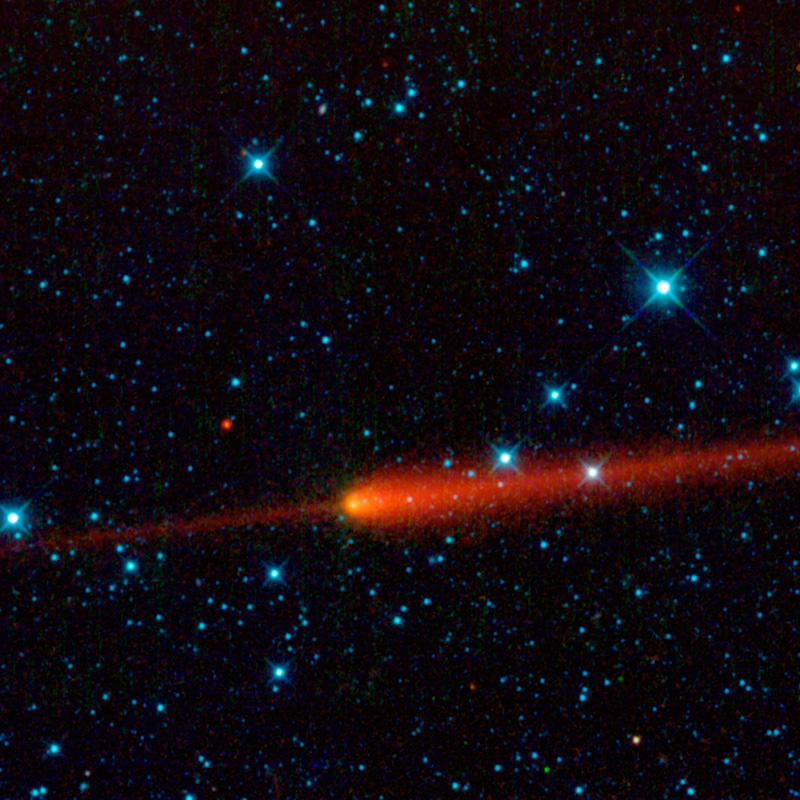

Comet 65/P Gunn

This image from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) features comet 65P/Gunn. Comets are balls of dust and ice left over from the formation of the Solar System. As a comet approaches the Sun it is heated and releases gas and dust from its surface. The gas and smallest dust particles are blown back by the solar wind into a long, spectacular tail. Comet 65P/Gunn’s tail is seen here in red trailing off to the right of the comet’s nucleus (near the center of the image).

Comet 65P/Gunn was discovered by James Gunn in 1970, who is the Project Scientist for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, another important survey of the sky done in visible light. This observation of the comet was made by WISE on April 24, 2010 (just one month after its closest approach to the Sun) in the constellation Capricornus. This is a single-frame observation, covering an area of 1.5 by 1.5 full Moons (0.76 by 0.76 degrees).

This comet is what is called a short-period, Jupiter family comet. It orbits the Sun inside the main asteroid belt between the orbits of the planets Mars and Jupiter. The orbit of 65P/Gunn is relatively round compared to many comets, and it takes 6.79 years to complete one trip around the Sun. At the time that this image was taken, the comet was at a distance from Earth of 392 million kilometers (243 million miles). For reference, the average distance between the Sun and Earth is 150 million kilometers (93 million miles). The comet’s speed, relative the Sun, when this picture was snapped was about a whopping 7,700 km/hr (4,800 mph).

Just ahead of the comet is an interesting fuzzy red feature that makes it look something like a swordfish, or narwhal. This “sword” is made of dust particles that have previously been shed by 65P/Gunn as it orbits the Sun, this is called a debris trail. Comet debris trails were discovered by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS). The Gunn debris trail was first observed by WISE science team member Russ Walker in the IRAS survey. It was later observed by astronomers using the Spitzer Space Telescope.

The dust in a debris trail is warmed by sunlight and glows in infrared light. Trails like this one often can nearly encircle the Sun, following the orbital path of the comet that produced it. Trails appear both ahead and behind the comet’s nucleus and have a narrow, contrail-like appearance. They represent the first stages in the evolution of meteoroid streams. Over time, the material in the debris trail can drift away from the comet’s orbit and become clouds of debris that will be seen as a meteor shower if Earth passes through it.

Also visible in this image are several asteroids—chunks of rock and metal leftover from the formation of the Solar System—all of which orbit the Sun in the main asteroid belt. Asteroids are much cooler than stars and appear red in this image. The most prominent asteroids in the image are: (2661) Bydzovsky, (76826), (E4813) , and 2007 VG119.

WISE sees invisible infrared light, and all four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this image. The colors are representational. In this image, 3.4-micron light is colored blue; 4.6-micron light is green; 12-micron light is orange; and 22-micron light is red. Bluer objects in this image are warmer in temperature, like stars, and cooler objects, like asteroids and the comet, are redder in appearance.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

- neufer

- Vacationer at Tralfamadore

- Posts: 18805

- Joined: Mon Jan 21, 2008 1:57 pm

- Location: Alexandria, Virginia

Johnny Got His Gunn

[list]Johnnie, get your Gunn,

Get your Gunn, get your Gunn,

Take it on the run,

On the run, on the run.

http://www.firstworldwar.com/audio/overthere.htm[/list]

Get your Gunn, get your Gunn,

Take it on the run,

On the run, on the run.

http://www.firstworldwar.com/audio/overthere.htm[/list]

Art Neuendorffer

Re: WISE: Comet 65/P Gunn

P Gunn

Click to play embedded YouTube video.

- neufer

- Vacationer at Tralfamadore

- Posts: 18805

- Joined: Mon Jan 21, 2008 1:57 pm

- Location: Alexandria, Virginia

That's Shikles...Gail Shikles

http://www.briansdriveintheater.com/craigstevens.html wrote:

<<Born Gail Shikles in Liberty, Missouri, on July 8, 1918, Craig Stevens originally intended to be a dentist were it not for the drama classes he began taking at the University of Kansas in the late 1930s. Leaving college, Stevens went to California and, through his work at the Pasadena Playhouse, eventually found work in films. His film appearance came in a brief bit in Columbia's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. During World War II, Stevens became a popular leading man in B movies and acted in a number of military shorts for the war effort. After the war, however, Warner Bros. stable of actors returned from military service, and Steven's career went into decline. Stevens' career stablized in the mid 1950s with roles in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953) and the campy horror flick The Deadly Mantis (1957). In 1958, Stevens was cast in the title role in the NBC noir series Peter Gunn, for which he's best remembered.>>

Art Neuendorffer

WISE: V385 Carinae: Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star?

V385 Carinae: Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star? - 17 June 2010

V385 Carinae: Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star?

Some might see a blood-red jellyfish in a forest of seaweed, while others might see a big, red eye or a pair of lips. In fact, the red-colored object in this new infrared image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is a sphere of stellar innards, blown out from a humongous star.

The star (white dot in center of red ring) is one of the most massive stellar residents of our Milky Way Galaxy. Objects like this are called Wolf-Rayet stars, after the astronomers who found the first few, and they make our Sun look puny by comparison. Called V385 Carinae, this star is 35 times as massive as our Sun, with a diameter nearly 18 times as large. It's hotter, too, and shines with more than one million times the amount of light.

Fiery candles like this burn out quickly, leading short lives of only a few million years. As they age, they blow out more and more of the heavier atoms cooking inside them -- atoms such as oxygen that are needed for life as we know it.

The material is puffed out into clouds like the one that glows brightly in this WISE image. In this case, the hollow sphere showed up prominently only at the longest of four infrared wavelengths detected by WISE. Astronomers speculate this infrared light comes from oxygen atoms, which have been stripped of some of their electrons by ultraviolet radiation from the star. When the electrons join up again with the oxygen atoms, light is produced that WISE can detect with its 22-micron infrared light detector. The process is similar to what happens in fluorescent light bulbs.

Infrared light detected by WISE at 12 microns is colored green, while 3.4- and 4.6-micron light is blue. The green, kelp-looking material is warm dust, and the blue dots are stars in our Milky Way galaxy.

This image mosaic is made up of about 300 overlapping frames, taken as WISE continues its survey of the entire sky -- an expansive search, sure to turn up more fascinating creatures swimming in our cosmic ocean.

V385 Carinae is located in the Carina constellation, about 16,000 light-years from Earth.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

Re: WISE: V385 Carinae: Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star?

Oh, that's great!!stellar innards

guts an' innards, innards an' guts.... and they're stellar, tooooooo

There's got to be a good children's song in there somewhere. <g>

A closed mouth gathers no foot.

-

hellogts

Re: WISE: V385 Carinae: Jumbo Jellyfish or Massive Star?

Science fiction...

Brad and Janet...

Brad and Janet...

WISE: M83 - Southern Pinwheel Galaxy

M83 - Southern Pinwheel Galaxy - 25 June 2010

M83 - Southern Pinwheel Galaxy

This image from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is of the nearby galaxy Messier 83, or M83 for short. It is a spiral galaxy approximately 15 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra. It is sometimes referred to as the southern Pinwheel galaxy. M101 is called the Pinwheel galaxy and M83 has a similar appearance, but it is located in the southern sky. At about 55,500 light-years across it is a bit more than half the size of the Milky Way Galaxy, but it has a similar overall structure.

Like the Milky Way, most of M83’s stars, dust, and gas lie in a thin disk decorated with grand spiral arms. We see the disk of M83 nearly face-on (whereas we see the disk of the Milky Way edge-on since we are inside it). The spiral arms are places where the disk is a little denser with stars and gas, which leads to a higher rate of star formation in them. Where there is star formation, we find more very bright, short-lived stars, and plenty of dust (green and red in this infrared image).

M83 also has a central bulge of stars and dust that has a component that is roughly spherical and a component that is shaped like a bar. So M83 is referred to as a barred spiral galaxy.

This image was made from observations by all four infrared detectors aboard WISE. Blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is primarily light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is primarily emission from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

WISE: The Tarantula Nebula

NGC 2070: The Tarantula Nebula - 01 July 2010

NGC 2070: The Tarantula Nebula

Sending chills down the spine of all arachnophobes is the Tarantula Nebula in this image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE). Located in the southern constellation of Dorado, the Tarantula Nebula is a giant star forming region in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

The Large Magellanic Cloud is an irregular dwarf galaxy that orbits the Milky Way. It is relatively close, in galactic terms, at about 160,000 light-years. Its motion around the Milky Way causes compression of interstellar dust and gas at is leading edge. This has led to the huge burst of star formation creating the Tarantula Nebula.

At about 1,900 light-years across, the Tarantula Nebula is the largest star forming region known in the entire Local Group of galaxies, a region encompassing over 30 galaxies including the great galaxy in Andromeda. In 1987, the closest supernova observed since the invention of the telescope was seen at the edge of the Tarantula Nebula (SN1987A). It was determined to be the violent explosion of a very massive star.

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. The image spans an area of 1.4 x 1.2 degrees on the sky or about 3 times as wide as the full Moon, and 2.5 times as high. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

WISE: Tycho’s Supernova Remnant

SN 1572: Tycho’s Supernova Remnant | 09 July 2010

This image from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) takes in several interesting objects in the constellation Cassiopeia, none of which are easily seen in visible light.

The red circle visible in the upper left part of the image is SN 1572, often called “Tycho’s Supernova”. This remnant of a star explosion is named after the astronomer Tycho Brahe, although he was not the only person to observe and record the supernova. When the supernova first appeared in November 1572, it was as bright as Venus and could be seen in the daytime. Over the next two years, the supernova dimmed until it could no longer be seen with the naked eye. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the remnants of the supernova could be seen again with the help of telescopes.

When the star exploded, it sent out a blast wave into the surrounding material, scooping up interstellar dust and gas as it went, like a snow plow. An expanding shock wave traveled into the surroundings and a reverse shock was driven back into toward the remnants of the star. Previous observations by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope indicate that the nature of the light that WISE sees from the supernova remnant is emission from dust heated by the shock wave.

In the center of the image is a star forming nebula of dust and gas, called S175 (in the Sharpless catalog of ionized nebula). This cloud of material is about 3,500 light years away and 35 light-years across. It is being heated by radiation from young hot stars within it, and the dust within the cloud radiates infrared light.

On the left edge of the image, between the Tycho supernova remnant and the very bright star, is an open cluster of stars, King 1, first catalogued by Ivan King, an astronomer at UC Berkeley. This cluster is about 6,000 light-years away, 4 light-years across and is about 2 billion years old.

Also of interest in the lower right of the image is a cluster of very red sources. Almost all of these sources have no counterparts in visible light images, and only some have been catalogued by previous infrared surveys. There are indications that they may be young stellar objects associated with a dense nebula in the area. Young stellar objects (YSOs) are stars in their earliest stages of life. YSOs are surrounded by an envelope of dust, which would explain the very red color of the sources in this image.

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. The image spans an area of 1.6 x 1.6 degrees on the sky or about 3 times as wide and high as the full Moon. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

WISE: The Pleiades: Seven Sisters Get WISE

The Pleiades: Seven Sisters Get WISE | 16 July 2010

This image shows the famous Pleiades cluster of stars as seen through the eyes of WISE, or NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. The mosaic contains a few hundred image frames -- just a fraction of the more than one million WISE has captured so far as it completes its first survey of the entire sky in infrared light.

The Pleiades are what astronomers call an open cluster of stars, meaning the stars are loosely bound to each other and will eventually, after a few hundred million years, go their separate ways. The cluster is prominent in the sky during winter months in the constellation Taurus, when viewed from the Northern Hemisphere. Often called the Seven Sisters from Greek tradition, this cluster of stars has been named by cultures the world over: Parveen in Persian; Tianquiztli in the Aztec tradition, and Subaru in Japan. The Pleiades is even the logo of the automotive company that bears its Japanese name.

In this infrared view of the Pleiades from WISE, the cluster is seen surrounded by an immense cloud of dust. When this cloud was first observed, it was thought to be leftover material from the formation of the cluster. However, studies have found the cluster to be about 100 million years old -- any dust left over from its formation would have long dissipated by this time, from radiation and winds from the most massive stars. The cluster is therefore probably just passing through the cloud seen here, heating it up and making it glow.

At a distance of about 436 light-years from Earth, the Pleiades is one of the closest star clusters and plays an important role in determining distances to astronomical bodies further away. This picture from WISE covers an area of 3.05 by 2.33 degrees, which is the roughly the same area on the sky that a grid of six full moons by 4.7 full moons would occupy. Most of the stars in the cluster fall within the 20-light-year-wide region shown here.

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

Re: WISE: The Pleiades: Seven Sisters Get WISE

The Seven WISE Sisters

Bad Astronomy | 19 July 2010

Bad Astronomy | 19 July 2010

If you live in the northern hemisphere and go outside in the winter, hanging not too far from Orion’s left shoulder is a small, tight, configuration of stars. A lot of people mistake them for the Little Dipper — I get asked about it all the time — but really it’s the Pleiades (pronounced PLEE-uh-dees), an actual cluster of stars about 400 light years away. To the eye you can usually spot six of the stars (the seventh, seen in ancient times, may have faded a bit since then), and in binoculars you can see dozens.

But when NASA’s Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) looked at it in February, this is what it saw: (right)

Coooool. Literally! WISE looks in the infrared, and can see cool objects that are invisible to our eyes. The Pleiades stars are bound together in a cluster by their own gravity, and are currently plowing through a dense cloud of dust and gas in the galaxy. The material has been warmed up by the hot stars, and glows in the infrared. Deep images in visible light also show the material, but it looks blue as it reflects the optical light from the stars. In the WISE images, we’re seeing the matter actually glowing on its own, emitting infrared light.

When I was younger it was thought that this material was the leftover stuff from which the stars formed. But it was later found that the stars are older than first thought; about 100 million years old. While still quite young — the Sun is 4.5 billion years old! — that’s long enough for the original cocoon of material that made up these stars’ nursery to have dispersed. So it’s a cosmic coincidence that we happen to see the cluster as it’s ramming through this material. On the other hand, the Milky Way galaxy is loaded with lots of junk floating out there, and the Pleiades are in an area of high traffic. It’s not too surprising we’d see something like this happening, and it’s nice that it’s going on close enough that we get a good view of it.

WISE doesn’t just get pointed wherever astronomers see something interesting: it’s an all-sky survey, spinning on its axis and taking snapshots continuously. These are stored, and astronomers on the ground can then put them together in a mosaic. This image is actually pretty big, covering 2×3° of the sky. That’s about the size of a postage stamp held at arm’s length, and is a fair bit bigger than the full Moon on the sky. This image was released to celebrate the fact that as of July 17, WISE has now scanned the entire sky, and its primary mission has been fulfilled. Yay!

Funny, too: I’ve observed the Pleiades a lot, and seen lots of pictures too, yet it’s difficult to identify the stars in the WISE image — I had to rotate the visible image to match the one from WISE, but even then it’s not entirely obvious how they line up. In the IR, stars are bright that might be dim in optical, and vice-versa! But I’d recognize the sheets and filaments of the disturbed dust anywhere. One of my favorite things in astronomy is seeing a familiar object in an unfamiliar way. It reminds me that there’s still plenty to learn about the Universe.

Re: JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases

Unsurprisingly, I strongly dislike the WISE image of the Pleiades because it takes one of the loveliest and truly bluest naked-eye objects in the sky and turns it into something messy-looking and non-blue.

Phil Plait said:

I think an image of this seems to be rather pointless. I can certainly understand astronomers who use infrared astronomy to find brown dwarfs in the Pleiades, but I don't get why people would simply want to color the lovely blue reflection nebula non-blue and make the sparkling bright blue stars look faint - I don't understand the point of it.

Ann

Phil Plait said:

And I guess the WISE team took that infrared image of the Pleiades in order to learn something about that cluster. So what, then, did they learn? Clearly the Merope nebula is differently colored (cooler?) than the rest of the nebula, which is perhaps no great surprise since the Merope Nebula is the thickest, densest part of the Pleiades nebulosity.One of my favorite things in astronomy is seeing a familiar object in an unfamiliar way. It reminds me that there’s still plenty to learn about the Universe.

I think an image of this seems to be rather pointless. I can certainly understand astronomers who use infrared astronomy to find brown dwarfs in the Pleiades, but I don't get why people would simply want to color the lovely blue reflection nebula non-blue and make the sparkling bright blue stars look faint - I don't understand the point of it.

Ann

Color Commentator

Re: JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases

You guess wrong. The image is a composite made from images taken from the complete infrared sky scan being made by WISE.Ann wrote:Unsurprisingly, I strongly dislike the WISE image of the Pleiades because it takes one of the loveliest and truly bluest naked-eye objects in the sky and turns it into something messy-looking and non-blue.

Phil Plait said:

And I guess the WISE team took that infrared image of the Pleiades in order to learn something about that cluster. So what, then, did they learn? Clearly the Merope nebula is differently colored (cooler?) than the rest of the nebula, which is perhaps no great surprise since the Merope Nebula is the thickest, densest part of the Pleiades nebulosity.One of my favorite things in astronomy is seeing a familiar object in an unfamiliar way. It reminds me that there’s still plenty to learn about the Universe.

I think an image of this seems to be rather pointless. I can certainly understand astronomers who use infrared astronomy to find brown dwarfs in the Pleiades, but I don't get why people would simply want to color the lovely blue reflection nebula non-blue and make the sparkling bright blue stars look faint - I don't understand the point of it.

Ann

Do you have something against science?

Phil Plait in [i]The Seven WISE Sisters[/i] wrote:WISE doesn’t just get pointed wherever astronomers see something interesting: it’s an all-sky survey, spinning on its axis and taking snapshots continuously. These are stored, and astronomers on the ground can then put them together in a mosaic. ... This image was released to celebrate the fact that as of July 17, WISE has now scanned the entire sky, and its primary mission has been fulfilled. Yay!

[i]WISE: The Pleiades: Seven Sisters Get WISE[/i] wrote:This image shows the famous Pleiades cluster of stars as seen through the eyes of WISE, or NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. The mosaic contains a few hundred image frames -- just a fraction of the more than one million WISE has captured so far as it completes its first survey of the entire sky in infrared light.

...

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Re: JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases

To see what else is there, of course! Our eyes can see just a narrow part of the whole spectrum, and though you want to remain blind to what else might be out there that isn't in visible light, others don't. You'd rather see the reflection than the glow. Fortunately, you can, and yay! for that! Why complain, then, about images which show the glow rather than the reflection?Ann wrote:I don't get why people would simply want to color the lovely blue reflection nebula non-blue and make the sparkling bright blue stars look faint - I don't understand the point of it.

A closed mouth gathers no foot.

- Chris Peterson

- Abominable Snowman

- Posts: 18587

- Joined: Wed Jan 31, 2007 11:13 pm

- Location: Guffey, Colorado, USA

- Contact:

Re: JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases

It is exactly as pointless as taking an image in visual light, I guess.Ann wrote:I think an image of this seems to be rather pointless.

In fact, this IR image shows a vast amount of structure that is invisible in any image made at shorter wavelengths. In the visible, we only see structure in the dust that is close enough to stars to be brightly lit. In the IR, the structure of the cloud is visible over a far greater extent, including regions much further from any bright stars.

That's because your sense of aesthetics seems narrowly limited to the way your eye works. You apparently don't appreciate the additional knowledge an image like this provides. What would be pointless would be to put up an IR telescope and then refuse to point it at the Pleiades. What would be pointless would be to shoot an image in the IR and then limit our own ability to detect structure by painting that image blue (just because blue is our favorite color).I can certainly understand astronomers who use infrared astronomy to find brown dwarfs in the Pleiades, but I don't get why people would simply want to color the lovely blue reflection nebula non-blue and make the sparkling bright blue stars look faint - I don't understand the point of it.

IMO, aside from the scientific data this image has added to our knowledge, the image itself is spectacularly beautiful. The fact that we have images of the Pleiades covering the UV to radio is beautiful as well.

Chris

*****************************************

Chris L Peterson

Cloudbait Observatory

https://www.cloudbait.com

*****************************************

Chris L Peterson

Cloudbait Observatory

https://www.cloudbait.com

Re: JPL: WISE Mission Image Releases

I agree, wholeheartedly! Strangely, I find the one line that Ann picked out from Phil's blog most apropos. Pity she can't appreciate the beauty of such images.Chris Peterson wrote:IMO, aside from the scientific data this image has added to our knowledge, the image itself is spectacularly beautiful. The fact that we have images of the Pleiades covering the UV to radio is beautiful as well.

Phil Plait wrote:One of my favorite things in astronomy is seeing a familiar object in an unfamiliar way. It reminds me that there’s still plenty to learn about the Universe.

- neufer

- Vacationer at Tralfamadore

- Posts: 18805

- Joined: Mon Jan 21, 2008 1:57 pm

- Location: Alexandria, Virginia

Re: WISE: The Pleiades: Seven Sisters Get WISE

Me too.bystander wrote:The Seven WISE Sisters

Bad Astronomy | 19 July 2010

Art Neuendorffer

WISE: Vela A: WISE Peers Into the Stellar Darkness

Vela A: WISE Peers Into the Stellar Darkness | 26 July 2010

Vela A: WISE Peers Into the Stellar Darkness

New stars are forming inside this giant cloud of dust and gas as seen in infrared light by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. Sprawling across the constellation Vela is a complex of dark, dense clouds of dust and gas, difficult to detect with telescopes that see only visible light. The complex is called the Vela Molecular Cloud Ridge. This ridge may form part of the edge of the Orion spiral arm spur in the Milky Way Galaxy. Astronomers mapping out the region in radio light in the late 1980s found four distinct regions of the densest gas and named them clouds A, B, C and D. This image takes in the first of those clouds, Vela A.

Vela A is about 3,300 light-years away. This image of Vela A covers a region on the sky over 4.5 full Moons wide and over 3 full Moons tall, spanning about 130 light-years in space. The core of the cloud is being excavated by the radiation and winds from hot, young stars. The energy from the new stars is absorbed by the surrounding dust. This hides them from view in visible light, but the heated dust glows in infrared light (seen here in green and red). Sprinkled around Vela A are a few groups of sources that appear very red in this image, and have no known counterparts in visible-light images of the region. It’s possible that these may be Young Stellar Objects, which are stars in their very infancy enveloped in dust. The infrared light seen from these baby stars does not come directly from the stars, but rather from the dust around them, which glows as the nascent stars heat it.

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

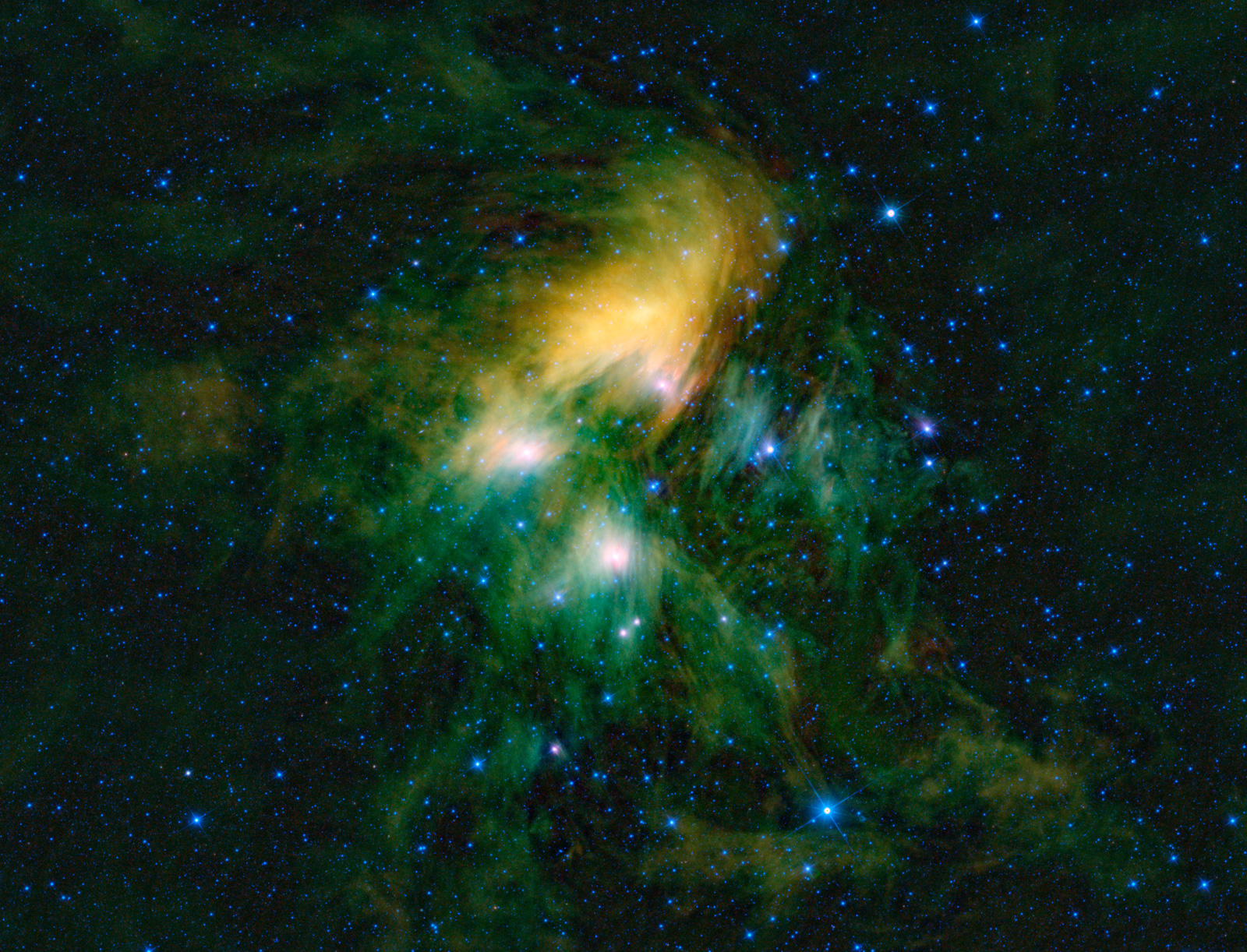

AFGL 490: WISE Reveals a Hidden Star Cluster

AFGL 490: WISE Reveals a Hidden Star Cluster | 02 Aug 2010

WISE Reveals a Hidden Star Cluster

The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, has seen a cluster of newborn stars enclosed in a cocoon of dust and gas in the constellation Camelopardalis. The cluster, AFGL 490, is hidden from view in visible light by the cloud. But WISE’s infrared vision sees the glow of the dust itself, and penetrates this dust to see the infant stars within.

Not much is known about this stealthy star cluster. Its distance from Earth is estimated to be about 2,300 light-years. The portion of the star-forming nebula captured in this view stretches across about 62 light-years of space.

All four infrared detectors aboard WISE were used to make this mosaic. Color is representational: blue and cyan represent infrared light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns, which is dominated by light from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team

NGC 292: Small Magellanic Cloud

NGC 292: Small Magellanic Cloud | 09 Aug 2010

Small Magellanic Cloud

This image captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) highlights the Small Magellanic Cloud. Also known as NGC 292, the Small Magellanic Cloud is a small galaxy about 200,000 light-years away.

The Small Magellanic Cloud is named after the Portuguese explorer Fernando de Magellan who observed it on his voyage around the world in 1519. Since it is visible to the naked eye in dark-sky conditions, it is likely that people in the southern hemisphere observed the galaxy long before Magellan recorded it.

Located in the constellation Tucana, the Small Magellanic Cloud looks like a wispy cloud that circles the south celestial pole. Nearby, but not visible in this image, is the Large Magellanic Cloud, which is a sister galaxy to the Small Magellanic Cloud. Astronomers originally thought that both galaxies were orbiting the Milky Way Galaxy. But recent research suggests that they might be moving too fast to be bound by the Milky Way’s gravity and are passing by for the first time.

This WISE image illustrates why the Small Magellanic Cloud is considered an irregular galaxy. Galaxies are classified according to their shape, such as spiral or elliptical. Irregular galaxies don’t fit into any of these categories -- they are unique in shape.

The two streaks seen in the upper half of the image are satellites orbiting Earth, which happened to pass in front of the Small Magellanic Cloud when WISE captured this view.

This mosaic image was made from all four infrared detectors aboard WISE. The color in this image represents different wavelengths of infrared light. Blue and cyan represent light at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns mostly emitted from stars. Green and red represent light at 12 and 22 microns, which is mostly light from warm dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team